ALLEGORIES FOR THE IDEAL CHRISTIAN RULER: EMBLEM II. AD OMNIA. How, And When To Begin The Education Of A Young Prince

ALLEGORIES FOR THE IDEAL CHRISTIAN RULER

EMBLEM II. AD OMNIA.

How, And When To Begin The Education Of A Young Prince

With Pencil and Colours Art admirably expresses everything. Hence, if Painting be not

Nature, it certainly comes so near it as that

often its works deceive the sight, and are not to be

distinguished but by the touch. It can't, it's true, animate Bodies, but it frequently draws the Beauty, Motions and Affections of the Soul. Altho' indeed it cannot

entirely form the Bodies themselves for want of matter, yet the Pencil so exquiíitely deícribes them on

Canvas, that besides Life there's nothing that you can

desire more. Nature I believe would envy Art if she

could possibly do the fame, but now she is so kind, as

in many things to use the Assistance of Art; for whatever the Industry of this can perfect, that Nature does

not finish herself.

Thus we see man is born without

any manner of knowledge or propriety of speech, instruction and learning being left to draw the lineaments of of Arts and Sciences on his mind as on a blank Canvass, and Education to Imprint morality thereon, not

without great advantage to humane Society; for

hence it comes to pass that by One man's having Occasion for the Assistance of another, the bonds of

gratitude and affection are strengthened: for Nature

has sown the seed of Virtue and knowledge in all

of us, we are equally born to thofe goods of the

mind, which must be cultivated and quicken'd by some

other hand (1).

(1) Omnibus natura fundamenta dedit, fetnenque itrtutum, emnef ad ifla omnia natr fnmu<\ cum i rut, it or accejfit, tunc ilia artini bona, velut fvpita excitantur. Sen. Epist. 10.

But tis necessary these measures

be taken in the tender years, while the mind is fitter

to Receive all manner of forms, so readily apprehensive of sciences as to appear rather to remember than

first learn them; which Plato made use of as an argument to prove the immortality of the Soul (2); but if

this be neglected in the first Age, the affections by degrees get ground, and their depraved inclinations make so deep an impression upon the will as no education

can efface. The Bear no sooner whelps but licking the

limbs of her deformed Litter while they are soft, perfects

and brings them to shape, whereas if she suffered them

to grow firm her pains would be ineffectual.

(2) Ex hoc pop,} cogmjet an:mat iwnnrtales tffi, atque dtnn.it, quod in jHtOll mobilfa junt ingenia, ¿7 ad pe\ uyendttni fad lia. Fiar, dv A.u. taiy

It was

wisely done {in my Judgment) of the Kings of Persia

to Commit their Sons in their Infancy to Masters,

whose care it should be for the first seven years of

their life to Organize their Bodies: In the fecond to

strengthen them by using them to fencing and the like

Exercises. To these they after added four select Persons

to give the finishing strokes; the first eminent for Learning, made 'em Scholars; the fecond a discreet, sober

mnn, taught them to govern and bridle their appetites;

the third a Lover of Equity, inculcated the Administration of Justice; lastly the fourth eminently Valiant

and Experienced in Warfare, instructed them in Military Discipline, especially endeavouring by incentives

to Honour, to divert their minds from fear and Cowardice. But this good Education is particularly necessary in Princes as they are the Instruments of Politics

happiness and public safety. In others the neglect of

a good Education is only prejudicial to single persons

or at least influences very few: but in a Prince 'tis

not only against his private, but everyone's common

interest, whilst fome he injures immediately by his

Actions, others by his Example.

Man well Educated

is the most divine Creature in the World; If ill, of all

animals the most savage (3). What, I pray, can you

expect from a Prince who is ill Educated, and has got

the supreme power in his hands? other evils of a

Common wealth are of no long continuance, this

never terminates but with the Prince's life. Of what

Importance a good and honourable Education is, Philip

King of Macedón was sensible, declaring in his Letters

to Aristotle upon the Birth of his Son Alexander his Obligation to the Gods, not so much for giving him a

Son, as that he was born at a time when he could make

use of such a Master, and 'tis certainly never convenient to leave nature otherwise good, to herself and

her own operations, since the best is imperfect and requires some external industry to cultivate it, as indeed

do most things necessary for man's well being. The

punishment derived to us by the fault of our first parents being not to enjoy anything without labour and

the sweat of the Brow, how can you expect a Tree to

bear sweet fruit unless you transplant it, or by grafting it upon stems of a more refined and generous

nature, correct its Wildness. Education improves the

good and instructs the bad (4). This was the reason why Trajan became so eminent a Governour, because he added industry to his natural parts and had

the direction of such a Master as Plutarch. Nor had

King Peter firnamed the Cruel, ever proved so barbarous and tyrannical had John Alphonso, Duke of Albuquerque, his Tutor, known how to mollify and break his

haughty temper.

(3) Homo rectam rutins inflitutionern divmffimum manjuetiflimumque animal efjici folct ; fi vero, vel non fufficienter, vel ,non bene educetur % éomm qn£ terraprogenuit, feroaflimum. Piar. lib. 3. de leg.

(4) Ed^catio % fa tntUtuth ccmmoda.naturas bonas, ivduál, fa rurfum borne n at une ft talent inliitutionem confequantut , meliores adhuc fa prjijiantions evat/ire fimus. Piai. \)u\. 4 dc Leg.

There's the same difference in Mens

dispositions as in Metals, some of which are proof against fire, others dissolve in it; yet all give way to the

graving tools, are malleable and duótile. So there's no humour so rugged but care and correction may have

some effect on. Altho' I confess Education is not always sufficient of itself to make men Virtuous, because many times under Purple as among Briars and Woods,

there spring up such monstrous Vices, particularly in

persons of a great Spirit, as prove utterly Incorrigible.

What is more obvious than for young men to be debauched by Luxury, Liberty or Flattery in Princes Courts,

where abundance of Vicious affections grow as Thorns,

as noxious and unprofitable weeds upon ill manured

Land.

Wherefore Except these Courts are well instituted the care taken in a good Education will be to

very little purpose; for they seem to be like Moulds

and accordingly fo Form the Prince as themselves are

Well or ill disposed, and those Virtues or Vices which

have once began to be in repute in them, their ministers transmit to posterity. A Prince is scarce Master

of his reason when his Courtiers out of flattery Cry

up the too great Liberty of his Parents and Ancestor recommending to him some great and renowned Actions of theirs, which have been as it were the propriety

of his Family. Hence also it comes to pass that some

particular Customs and Inclinations are propagated

from Father to Son in a continued succession, not so much by the Native force of their blood, (for neither

length of time nor Mixtures of Marriage are used to

Change them ) as because they are established in the

Courts where Infancy imbibes them and as it were

turns them into nature, thus among the Romans the

Claudii were reputed Proud, the Scipio's Warlike, the

Appi ambitious; as now in Spain the Gusmans are looked upon to be Good Men, the Mendozas Humane,

the Maurices have the Character of Formidable, the

Toletan's Severe and Grave.

The same is Visible in

Artificers, when any of a family have attained an Excellency, they easily transmit it to their Children, the

Spectators of their Art and to whom they leave their

Works and Monuments of their Labour. To all this may

be added, that Flattery mixt with Error sometimes commends in a Boy for Vertue what by no means deserves

that name, as Lewdness, Orientation, Iniblence, Anger,

Revenge and other Vices of the like nature, some men

erroneously persuading themselves that they are tokens

of a great Spirit; which withall induces 'em too eagerly

to pursue these, to the neglect of real Virtues: as a

Maid sometimes if she be commended for her free

Carriage or Confidence, applies herself to those rather

than Modesty and Honesty, the principal good Qualities

of that Sex. Tho' indeed young men ought to be driven

from all Vices in general, yet more especially from

those which tend to Laziness or Hatred they being

more easily imprinted in their minds (5). Care therefore must be taken that the Prince over-hear no filthy

or obscene expressions, much less should he be suffered

to use them himself: We easily execute what we make

familiar to us in discourse, at least something near it (6).

Wherefore to prevent this Evil the Romans used to

Choose out of their families somme grave Ancient Matron to be their Sons Governess, whose whole Care

and Employment was to give them a good Education,

in whose presence it was not allowable to speak a foul

word or admit an indecent Action (7). The design of this severe discipline was that their nature being preserved pure and untainted, they might readily embrace honest professions (8) .

(5) Carina igitur mala, fed ea máxime qua turpitudinem habent vel odium parent, funtprocul a pu:ris removendt. Arirt. Pol. 7.C if.

(6) Ham f'cite tmpia hquendo, efficitur ut homines his próxima facicnr. Ariit. Pol. 7,0. 17.

(7) Coram qua neque dkere fas e at, qtod turpe dittit, ñeque faceré quod inhonejiumfttta viiintwr* ^uiar.dial, de orar. -

(8) j^f» difciplina, ac feve ritas eo peitinebat y ut fiicera ¿r integra, & nulJis pravitatibus detorta unii'fcujufque natura tnto fta'im pífíire arriperet ai tes hone/las. Quimil. Ibid.

Quintilian laments the

negled of this manner of Education in his time,

Children being usually brought up among servants,

and so learning to imitate their Vices. Nor, fays he, is

any one of the family concerned what he says or does

before his young Master, since even their parents don't

ib much inure them to Vertues and Modesty as Lasciviousness and Libertinism (9) . Which to this day

is usual in most Princes Courts: nor is there any

remedy for it, but displacing those Vicious Courtiers

and substituting others of approved Vertue who may

excite the Princes mind to Actions more generous and such as tend to true honour (10). When a Court

has once bid adieu to Vertue, 'tis often Changed but

never for the better, nor does it desire a Prince better

than it self. Thus Nero's family were Favourers of

Otho, because he was like him (11).

(9) Nee quifquam in tota domo p:nji habct quid

toram infante domino, ant dicat aut faciat ; quandn etiam ipfi pjrentes,

nee probittui ñeque modeJtU párvulo) ajfuefacunt, fed Utfcivis, *r iiber-

tati. Quint, ibid.

(10) Nt'q-- enim aurtbus jocunda conven'u dicere,fed

ex quo aliquii gloriojus fiat, Linip. in Hippol.

(11) Proni in cum .¿.r.t

iftrms Ht/imile.Ti. Tac 1. Hift. * Mar. H it. Hii>.

But if the Prince

cannot do this, I think it were more advisable for

him to leave that Court, as we remember James the 1st. King of Arragon did, * when he saw himself Tyrannized over by those who educated and confined him

as it were in a prison: nor can I give those Courts

any other name, where the principal aim is to enslave

the princes will, and he is not suffered to go this way

or that by choice and at his own pleasure, but is forcibly guided as his Courtiers please, just as Water is

conveyed thro' private Channels for the sole benefit

of, the ground thro' which it passes.

To what purpose

are good natural Parts and Education, if the Prince is suffered to see, hear and know no more than his Attendance think fit? What wonder if Henry the 4th.

King of Castile proved so negligent and sluggish, so

like his Father John the Second in all things, after he

had been Educated among the same Flatterers that occasioned his Fathers male Administration?

Believe me,

'tis as imponible to form a good Prince in an ill

Court, as to draw a straight Line by a Crooked

square: there's not a wall there which some lascivious

hand has not sullied; not a Corner but Echoes their

dissolute Course of Life: all that frequent the Court:

are fo many Masters and as it were Ideas of the

Prince, for by long use and Conversation each imprint something on him which may either be to his benefit

or prejudice, and the more apt his Nature is to Learn,

the sooner and more easily he imbibes those domestic

Customs. I dare affirm that a Prince will be good

if his Ministers are so; bad if they be bad: an instance

of this we have in the Emperor Galba, who when he

light upon good Friends and Gentlemen, was governed

by them, and his Conduct unblameable; if they were

ill, himself was guilty of inadvertence (12).

(12) Amkornnr, libertorumq; ubi iv bonos incidí ffet, fine reprebenfme pawns, fi muliforent, vfc ¿id tullan i¿na>M. T

Nor will it suffice to have thus reformed living and

animate figures in a Court, without proceeding alfo to

inanimate: for tho' the graving Tool and Pencil are but

mute Tongues, yet Experience has taught us they are far

,more eloquent and persuasive. What an incitement to

Ambition is Alexander the great's Statue? how strangely

do pictures of Jupiter's lewd Amours inflame Lust? besides, for which our corrupt nature is blameable, Art

is usually more celebrated for chefe kind of things

than Virtuous instructive pieces; At first indeed the

excellency of the workmanship makes those pieces Valuable, but afterwards lascivious persons adorn the

Walls with them to please and entertain the Eyes.

There should be no statue or piece of painting allowed, but fuch as may Create in the Prince a

glorious Emulation (13). The Heroic Achievements

of the Ancients are the properest subjects for Painting,

Statuary and Sculpture; thoíé let a Prince look on

continually, thofe read; for Statues and Pictures arc

fragments of History always before our Eyes.

After the Vices of the Court have been (as far as

possible thus corrected, and the Princes humour and

inclinations well known, let his Master or Tutor endeavour to lead him to some great undertaking, sowing in his Mind Seeds of Virtue and honour so secretly, that when they are grown it will be difficult to

judge whether they were the product of Nature or

Art. Let them encourage Virtue with Honour, brand

Vice with Infamy and Disgrace, excite Emulation

by Example; these things have a great Effect upon

all Tempers, tho* more on some than others. Those who

are of a Generous disposition, Glory influences most;

the Melancholy, Ignominy; the Choleric, Emulation,

the Inconstant, Fear; the Prudent, Example; which

is generally of most efficacy with all, especially that of

Ancestors; for often what the Blood could not, Emulation does perform. 'Tis with Children as young trees

on which you must Graft a branch ( as I may fay )

of the same Father, to bring them to perfection.

These

Grafts are the famous examples which infuse into Posterity the Virtues of their Ancestors and bear excellent

fruit. That therefore it may be conveyed as it were

thro' all the Senses into the mind, and take deep Root

there, should be the particular industry of his Instructors, and consequently they are not to be proposed

to the Prince in ordinary Exhortations only or Reproofs,

but also in sensible objects. Sometime let History put

him in mind of the great Achievements of his Ancestors, the glory of which eternized in print may excite him to imitate them.

Sometimes Music (that sweet and wonderful Governeis of the passions ) playing their Trophies and Triumphs, will be proper to

Raiíe his Spirits. Sometimes let him hear Panegyricks

recited upon their Life, to encourage and animate him

to an Emulation of their Vermes, now and then reciting them himself, or with his young Companions Act

over their Exploits as upon a flage, thereby to inflame

his mind: for the force and efficacy of the action is

by degrees fo imprinted on him that he appears the

very fame whofe perfon he reprefents: Laftlylethim

play the part of a King amongft them, receive petitions, give audience, ordain; puniih, reward > command

or marihal an Army, beiiege Cities and give Battel.

In experiments of this nature Cyrus was educated from

a little Boy and became afterwards an eminent General. But if there be any inclinations unbecoming

a Prince discernible in his Infancy, he should have the

Company of such as are eminent for the opposite Virtues

to corred the Vices of his Nature ; as we fee a straight

Pole does the Crookedness of a tender Tree tyed to it.

Thus if the Prince be Covetous, let one naturally liberal

be always at his Elbow ; if a Coward, one bold and daring ; if timorous, one resolute and active ,• if Idle and

Lazy, one diligent and industrious: for those of that

Age as they imitate what they fee or hear, fo they also easily copy their Companions Customs. To

Conclude, in Education, of Princes too rough Reprehension and Chailifement is to be avoided as a kind

of Contempt. Too much Rigour makes men mean fpi*

rited ; nor is it fit, that he should be servilely subject: to

One Man, who ought to Comn^uid all. It was well

faid of King Alphonsus, Generous Spirits tire [carter correihd

by 'Words than blows , and love and refpeB thofe mcfl "who ufe

them so.

Youth is like a young borle that the Barnacle

hurts, but is easily governed by the gentler Bit. Besides that men of generous Spirits usually conceive a

secret horrour of those things they learnt through fear; on the contrary have an inclination and desire to try those

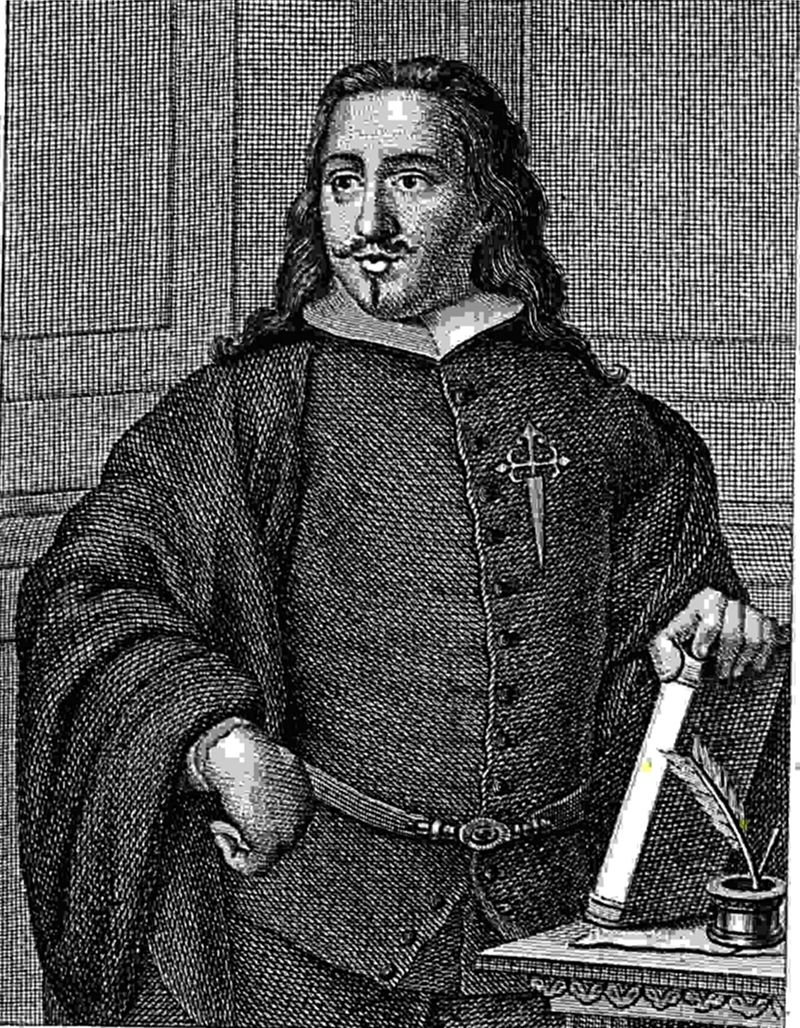

Empresas Políticas. Idea de un príncipe político cristiano ("Political Maxims. Idea of a Christian Political Prince")

Saavedra Fajardo, Diego de, 1584-1648

Comments

Post a Comment